“Hey, what was that?” I skidded to a halt, stopping so quickly that Nicola ran into me from behind. We found ourselves alone and breathless in the middle of old growth forest, no one else around for miles. The night was dark with that finality of nature, the moon lost in the thick canopy overhead. Summer heat still radiated from the ground below, but I felt the skin on my neck go cold. Somewhere across the valley, a familiar howl rose soft and sweet into the quiet air.

When Nicola Gildersleeve asked for some help running the Sunshine Coast Trail, I didn’t really believe her. I wanted to believe, but ten years is a long time. At the risk of sounding old, I’ve seen a lot of fools: a lot of other runners who tried to take the Sunshine Coast Trail end to end. A hundred and eighty kilometers of wilderness, of ancient paths and mossy cliffs, of working forests and non-working cellphones. Ean Jackson was the first, the first and best fool of them all. In 2004, he ran the entire shot in an exhausting 43 hours and 50 minutes, staggering into the Saltery Bay parking lot like a man on stilts. His pacers were half dead, his shoes were falling apart. The man was laughing. And because it was caught on film, his feat of endurance stood as an inspiration for us all. Named after Ean’s cheeky license plate, XS-NRG reached thousands of ultra runners, at the time when the sport was breaking out. From one to many, the gauntlet was thrown down.

Ean made it look easy, in a kind of laid back, clinically insane way. He rambled through the brush like a friendly bear, carefree and feeling fine. He dove into lakes, lost his pacers and went looking for them, had conversations with stumps. Instead of Shot Bloks and energy drinks, he scarfed down hamburgers and draft beer. If Action Jackson could do this trail, anyone could. Anyone who could run for two days straight without any kind of rest, that is. But ultra running was taking off, and there was suddenly no shortage of athletes. The film screened at VIMFF in Vancouver, and trail architect Eagle Walz dared participants to try it on for size. Many in the audience had run longer races with steeper climbs; the FatDog in BC’s interior, the iconic Tour du Mont Blanc in France. This was a romp in the backyard, an easy record for the taking. So they tried. But the Sunshine Coast Trail is not to be trifled with. In ten years, no one touched Ean’s record. No one even came close.

I got the message on Facebook, where all things begin. There were exclamation points, smiley faces. A stranger named Nicola was looking for runners to pace her on a record-breaking FKT across the Sunshine Coast Trail. I didn’t know what an FKT was (it’s Fastest Known Time, not a swear word), but I did know that she was making a goofy face in her profile picture. Several parties had already tried to the run the SCT this year only to fall back in disarray; I couldn’t remember if they had goofy Facebook faces. The breaking point seems to be about halfway through the route, as you leave the safety of the front coast behind. Your phone loses service, the land grows remote and wild, and you begin to realize that the only thing predicable about our trail is the incredible variety of randomness. Nicola Gildersleeve had never been past that point, and she was bringing along a few friends who were equally unfamiliar. I knew she had a chance, I wanted her to have a chance. Still, there was a reason that Ean’s record had held for so long. “I’m going to pace someone on the SCT,” I told my wife. “But there’s a 50/50 chance I won’t get started”.

I could afford to be cynical, because I was pacing her up the last and highest mountain of the run. At least, that was the plan. Then my phone began to ring. “Can you run tonight? Like, in a few hours?” Peter Watson sounded vaguely amused, which seems to be the closest he comes to panicking. Peter is Nicola’s long time partner, aid wrangler, and taxi driver, and he had a problem. The Day 1 pacers were tiring earlier than expected, and Nicola didn’t have an escort for the hills beyond Inland Lake. This was an important part of the route, mentally and physically. The trail is less generously marked, the terrain steeper and more wild. The night would meet her on those slopes, as Nicola entered her twelfth straight hour of running. It would be somewhat mean, although not unheard of, to strip away her pacers just before this stage. So I agreed to do it, I cleared my evening, and I got ready to run.

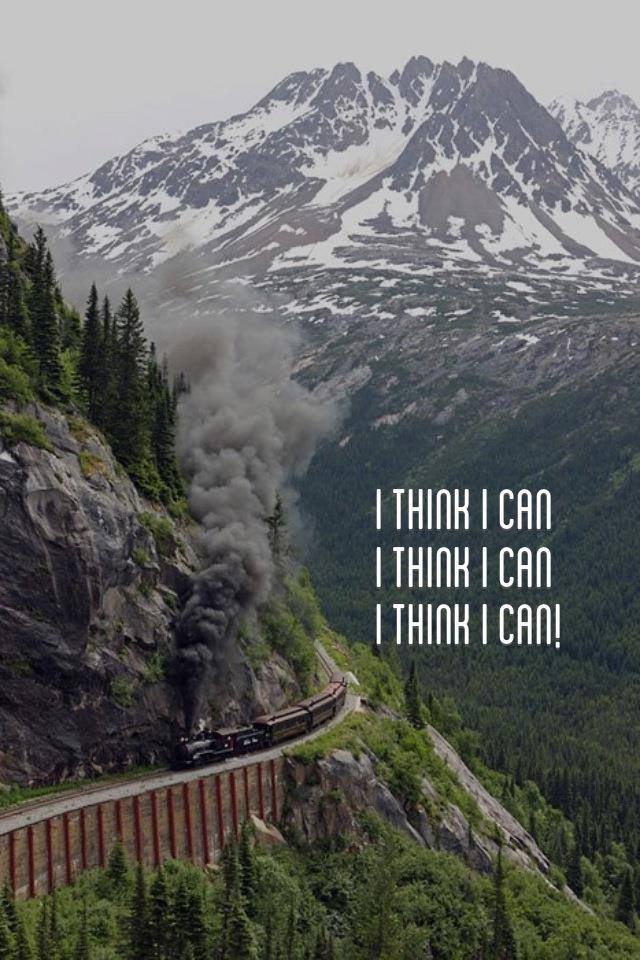

Pacing isn’t hard. You wait patiently at the rendez-vous point like a piece of baggage waiting for the train, and when that old train finally chugs into sight, you leap up and run really, really slow. Because unlike your sweaty companion, you are not in it for the long haul. You’re just tooling along for a few hours, heading for the next station down the line. Fresh eyes and local knowledge, until you get slightly winded and say goodbye. I thought about this as I laced up my shoes, untied them, then laced them up again. Pacing isn’t hard, at least, that’s what I heard. I had never actually paced anyone before.

I went to Inland Lake, and immediately I felt better. Because this person, this stranger who I would be leading through the dusk on an epic quest of daring-do, this woman wore the exact same shoes that I did. La Sportiva Crosslites are not very common. I got mine from the back aisles of MEC, but Nicola got hers right from the company. She was a La Sportiva sponsored athlete. This was the big leagues.

Imagine that you get up on stage to jam with a real musician, and she’s rocking the same guitar you have: that’s how I felt as Nicola ran into the aid station. And she looked completely fine. Like she was bounding off a magazine cover, not finishing her tenth hour of hills. I would have hardly believed it except for the pacer: My friend Meghan Molnar lead Nicola in, and Meghan was done. A strong, capable distance runner, Meghan came in saltier than potato chips, her face literally white with salt. The day was hot, pushing 30°. As Nicola complimented me on my shoes, Meghan walked in small circles towards the cool waters of Inland Lake, like a desert traveller crawling for an oasis. I remember my last marathon in that temperature, the effect on my body. You carry the sauna with you, unshakable and intense. The first pacers were done & down. I was up next.

We set a quick pace along the Inland lakeshore, the most runnable section of the entire trail. This was really going down, and now it was up to me. We started over the first bridge, and I switched smoothly into touring mode. If you run with me, you will get the tour: that’s how it works. “Watch the middle point, it’s slanted,” I said between breaths. “I was biking along in a windstorm, and a tree hit right here.” The old growth cedar had exploded on impact, breaking the bridge in two. I came along on my bike just five minutes later, hoisting it on my shoulders through the war zone. By the time I reached the parking lot, the lake was so calm it looked like glass. I stood with my camera for an hour, shooting photo after photo of the impossible horizon.

As I spoke, I settled on a pacing strategy. I’ve read enough reports from long races to know a little about what could be in her head, so I decided to keep her out of there as much as possible. This would be achieved by talking a lot, until she either told me to shut up or discovered new strength in outrunning me. By nature I am not a talkative person, but I was going to try. The history of the trail, local legends, random anecdotes, my own background in these woods, my childhood growing up. Everything was fair game to blab about, except The Question. I resolved to never, ever ask how she was doing/feeling/coping. Best to leave that be. We passed the totem pole, cobalt blue at the side of the trail. Our marker for the junction ahead. We left the water, turning our backs to the setting sun. And we began to climb.

Nicola slowed to a walk immediately. The whole time I was with her I never saw her move quickly uphill, changing the way I think about running ascents. We walked and talked up the side of Confederation Hill, until she began muttering to herself. Her pace faltered, began to wander a bit from side to side. “I feel like I’m bonking, but I’m not,” she said to me. It sounded like a sad confession. We were on steep logging road grade, fading moss and bracken. The shadow of Mt. Mahoney loomed above us. I gave her a bit of time to figure it out, and we walked together like a couple of old pensioners, slow, slower, slower still. I tried a few funny stories, which seemed to go down okay. Halfway through one of the funnier ones, I remembered that the punchline was about puking. Really, is that something I need to bring up right now? Could I be doing a better job at this? Ten minutes went by, and Nicola came back to herself. We picked our way along a rotting ladder in the side of the hill, began the switchback section beneath massive redwood cedars. We were high enough to reach the last rays of sunlight, deep orange and gold flooding through the stand. “It’s beautiful,” I whispered, half to myself. “It’s steep,” Nicola said. So pragmatic, these ultra runners. But she was back.

Dusk had fallen by the time we reached the next shore. Here I encouraged as much speed as possible, wanting to flee this section before darkness set in. Confederation Lake is small, and you can easily see the cabin at the far end. But the path is tangled, full of twists and turns. An impossibly old forest, free of brush and difficult to track through. We didn’t make it, pulling out our lights before we were even halfway around. This place has a name, marked on the old maps. The Valley of Fatigue. Still, there was a bit of a glimmer in the trees. Just enough light to win through. We crossed the last bridge to the baying of three enormous hounds, and Nicola’s dismay. “I don’t do well with dogs,” she whispered confidentially. So what are pacers for, but to blunder bravely forward and greet this wagging, wailing welcome committee. Their owner came out with apologies, pulling them back. Bears were in the neighbourhood, at least, he thought they were bears. Wouldn’t we stop a while at the cabin? No. I knew Nicola wouldn’t brag — we never brag — so I had to explain about her epic quest. Records will not be broken by stopping for tea in recreation cabins. On we went, past the open-air outhouse that looks strangely like a huge Fisher-Price potty. I had told Nicola about this earlier, and we both stood and laughed a long time at the funny potty toilet. I’m not sure why it was so funny, except for running. Running makes things pretty hilarious.

This was the true ending of the day, on the last open shore of Confederation Lake. As soon as we hit the trail, darkness reigned supreme. The markers were not very reflective to our little headlamps, and I strained my memory back to remember other days. Strolling with Katie after we woke in the forest dawn, or running with Steve on my almost-ultra in the mountains. We walked until I began to feel the trail again, began to expect the turns. And then we ran. Suddenly we burst out into the open, the far side of the bluff. Tin Hat mountain rose serene before us, where she would be some hours from now. Getting smarter, I didn’t tell Nicola that this bluff was Vomit Vista. She didn’t need to know that Eagle was violently sick here once, leading to its unique name. Some trivia was better off unsaid.

In the film, this place is where Ean Jackson’s run starts to go wrong. The climb to Confederation was too steep, the trail too thin and narrow. The daylight left them here, just as it left us. His pals were dismayed and demoralized, and they started dropping out. You have to respect that, you have to respect history. Even if the history is funny, with Ean carrying his friend Dave into the aid station like a man near death, hamming it up so that the rest of team thought they had a crises on their hands. Dave Cressman was fine, he just needed a good night’s sleep. A sleep I could look forward too, and Nicola could not. That old train had to keep on chugging.

We were descending from Confederation again, losing our hard-won elevation in fits and starts. The trail was gone before our eyes, hidden under a lush blanket of salal. I was guiding us mostly by toe, probing for the solidity of the path under my feet. To our right, the hillside fell away into darkness. I lost the trail a few times, lost Nicola only once when I forgot to slow down for a sudden rise. Looking back, I could see her headlamp moving as steady as a ship in the night. Cruising up the hill like that was all there was, like life was motion and motion was infinite. What a beautiful illusion, that we could live to move forever.

We passed from this into a sheer amphitheatre of hemlock and fir, the ground coloured like chocolate in our questing lights. Few markers, just a trace through the needles, piled deep along the trail. Years and years worth, like the spent seconds of our lives. I nearly went down a few times, dancing on my toes to stay upright. Nicola had no time for such frivolous movements, gliding along behind me. With every tired mile I found myself more impressed with her, the state she was in. Calm, focused, content in all we ran. She talked about pizza sometimes, but there didn’t seem to be much to complain about. The balance she brought was enormous. Around us, the forest was calm.

Confederation Hill separates the front country from all that lies beyond. No city lights, no phone signals. Darkness and memory. This is the first place I came when I was a child, all of six years old. Rolling into Powell River with my mom, we heard about a hippie festival going on far up the lake, a “Healing Gathering” at Fiddlehead Farm. The boat was leaving right then, so we got onboard. I was a city boy, fresh from Victoria. When the skiff let us down at the towering forest, I felt like I was climbing onto another world. Carrying my book bag, I followed a truly ancient road deep into the wilderness, heart wild in my chest. Now I was here again, in the shadow of the valley, looking for that same road. No farmhouses, no parties remained. The owners grew old and passed away, the lands were sold and logged and torn apart. Only the orchard survived, old fruit trees untouched by the ravages of time and fate. I was close to the orchard now, less than a kilometer away. But we were suddenly out of markers, lost on a connector that I was almost sure was right. This was a reroute, a section that had not been there before. “If I don’t see a marker in two minutes, we might be lost,” I admitted to Nicola. And then the distant howl, rising sweet and pure into the still night air. “Hey, what was that?”. Nic managed to stop mostly in time, only kicking me a little. We stood and listened to the mournful wail of… wait… car horns? The sound swelled and peaked, echoing through the valley. And then all was still. Was it a redneck party? A secret automotive dumping ritual? Or, somehow, “could that be for us?”. The only thing we knew was that it came from ahead, further up the old road. The road that even now was branching off, marked at last with the orange badge of the SCT. We were on the final trek, for me at least: the climb to Fiddlehead Orchard.

“Be careful on the corduroy bridges,” I called. They were old when I was six; now the logs were falling apart. Not rotting, but loosening in place, so that they jumped and jostled as we hurried across. I had been running for about three hours; Nicola, about 13. To have the land respond this way was beyond strange, and she almost balked. Little glints of water winked and shone from the cracks between them, but we carried on just the same. Balance unbroken. In a moment the path turned sharply left, a last dodge for the cutblocks that lay out there in the dark. An outhouse flew past as if on wings, and we were suddenly in the Fiddlehead Orchard. The trees untended by human hands, still hanging with fruit, crisp and sweet. Each year the orchard is a little bit smaller, as the forest consumes it. I still can find the old rope swing, hidden now amid the newly grown tangle of fir and hemlock. A ring of new life around old, caught and held in the wide expanse of logging that fills this valley. New howls rose ahead of us, human cheers and shouts from our happy aid team. It was almost time to say goodbye.

Our arrival was well timed, the crew only just in place. The dirt roads through Fiddlehead are a bit of a warren, and the two cars had become hopelessly separated. Lost from each other and the aid point, they resorted to desperate honking in the night, scaring their distant runners and finding each other with moments to spare. Now they were all set, and the action was pure pit-stop. They tossed Nicola in a chair, swapped out her shoes, taped up her feet, asked her a dozen questions, offered up a dozen strange treats. In the glow of shared headlamps I finally saw her face, almost a stranger’s face to me. We had been running single file for the whole jog, so that she was more of a voice, a bit of light behind me. Now I saw a woman just getting to her thirties, tall and fair, not as weather-beaten as most trail runners. She sat on her fabric chair like a tired queen, weary from campaigns upon the land. Her crown a misbehaving headlamp, which somehow at Hour 13 was no longer making sense. “I can’t figure out my headlamp”, she said mournfully to Peter, who was flitting around faster than my eye could follow. He got things straightened somehow, taped her feet up, massaged her shoes into place. He offered a fresh-made quesadilla, rescued from a miniature stove just before it burned. After a few minutes of this royal treatment, Nicola sighed, smiled, and pulled herself up. A full moon hung motionless on the horizon, blotting out the stars, filling the valley with light. She thanked me warmly, thanked her chief and team, thanked the new guy — Alston — for the pacing he was about to provide. She was not quite halfway done the course, but most of the elevation was still ahead of her. Her next steps would take her up Tin Hat mountain, and hours would pass until they were down the other side. No point in waiting around. They ran into the dark together, with just enough time to shout goodbye. The headlamps dwindled, went out. They were gone.

The team struck down the aid station in seconds, tossing food into coolers, rolling up the table. Soon the ground was bare again, and we were headed out on the long drive home. I left Peter at the crossing below Spring Lake, where Nicola would appear at some point in the prelude to dawn. Then Nicola’s mom drove us home, all the way down the mainline. Hours went by, and midnight rolled around. Somewhere far above us, Nicola and Alston were ambushing a herd of Elk, sending them scattering down the mountainside. Peter was enjoying his own adventure, as his tire went flat and then jammed on his truck, stranding him about 50 K from the nearest service station. He limped that truck down the road like a tired marathoner, until he was finally rescued by a passing hobo. Nearby Lois Lake has some interesting characters; this one had an 8 pound sledgehammer that got the tire off in a hurry. Then Eagle Walz swooped in, always the humble superman of the Sunshine Coast Trail. He brought his own truck, made sure Peter got to every trail section just on time. Ten years ago, his last-ditch pacing saved Ean’s run; now he was saving Peter’s aid. What is the definition of a superman? Among other things, it’s someone who knows exactly where he should be.

As for Nicola, well, she kept on chugging. Sometimes she was coughing, sometimes she was retching, but most of the time she was chugging. The sun came up as she was running off the Smith Range, heading for Mt. Troubridge and the final climb. I just so happened to be hiking there, and after a lot of glancing over my shoulder, Nicola and her latest pacer caught us at the 151 lookout. She had 29 kilometers to go, and she looked completely fine. Happy, calm, even kind of enthusiastic. “Only 8K up to the summit, so cool!”. We weren’t hiking to the summit that day (too damn far), but I knew she’d be there. As soon as I ran with her, I knew that she was going to finish. Baring death or dismemberment, Nicola Gildersleeve was going to finish. And she did.

At 33 hours and 50 minutes, Nicola ran to the Saltery Bay parking lot. She threw her tired arms wide, hugging the kiosk map like it was a long lost friend. And in a way, it was. Nicola didn’t conquer the SCT as much as she befriended it, welcomed it into her family. That’s just my perspective as a pacer, and I could be wrong. Maybe when I left, she beat her chest like Tarzan and yelled “Take that, SCT!”. Such behaviour would be justified. I mean, she knocked ten hours off a record that had stood unbroken for a decade. That doesn’t happen a lot. I may never see it happen again in my lifetime.

And Ean? He doesn’t mind a bit. Ever since he ran the course, Action Jackson has been waiting for someone who would do it all over again, and make it look easy. Besides, he even has a consolation prize. After today, Ean is still the fastest man.

When Nicola Gildersleeve asked me to help run the SCT, I didn’t quite believe her. I went anyway, because I wanted to believe. You won’t know until you try, and I wanted to support that try, that effort. Win or lose, it’s the effort that holds true greatness. I didn’t think it would mean that much, but at the end of the day this felt like something important. More than a race, more than a number on a wall. The strength that Nicola brought to our trail will stay with me a long time. Her clarity, her incredible sense of acceptance. A power that lives in all of us, to face whatever challenges wait in the path ahead.

That, and we wore the same shoes.

Very awesome account, Joseph. Thank you for sharing.

After 10 years of holding the record for the FKT, I can’t tell you how happy I am to get “chicked.” Congrats, Nicola!

I figured that by Nicola’s accomplishment of knocking almost exactly 10 hours off my time, I was done like dinner… relegated to the history books and the sands of time. Thanks for pointing-out that I am still the male record-holder! =;-)

Runners and hikers everywhere should know that some of those stunning groves of old growth on the Sunshine Coast Trail have fallen in the past 10 years. “Use it or loose it” most definitely applies. Run it. Hike it. Bring your friends. Use the Sunshine Coast Trail so it’s there for the future.

Thanks to the efforts of Eagle Walz and the many dedicated trail builders in and around Powell River, the trail has been manicured like a golf green. There are cabins along the way that serve as perfect aid stations. There’s an awesome craft brewery in Townsite, as well, so dehydration is not an issue.

Come on guys… The record is soft. It’s yours for the taking!

Such a pleasurable read!! Many thanks for another great story Jo!

Great work Nicola! Nice work documenting it Joseph – and good on you for being part of the team…

As an FYI, the photo credit on the SCT 2004 group shot goes to Paul Kennedy. Your post brings back great memories of that weekend. Next time I think Nicola and Jackson should run together – on Jackson’s diet…

Thanks Paul! That picture popped up on an image search for Ean & XS-NRG, without attribution. It’s a great shot.

Such a great account of this beautiful journey. I am cousins with Nicola and know her well; you payed wonderful homage to her spirit. Thank you for a lovely read.

awesome words!